Image source: Guldborgsund Kommune

In the previous blog we highlighted some of the key policy mechanisms that have been used to address food insecurity for key food system actors:

Agricultural producers > Price Incentives, Fiscal Support

Food environment > General Services Support, Other support

Consumers > Fiscal Support

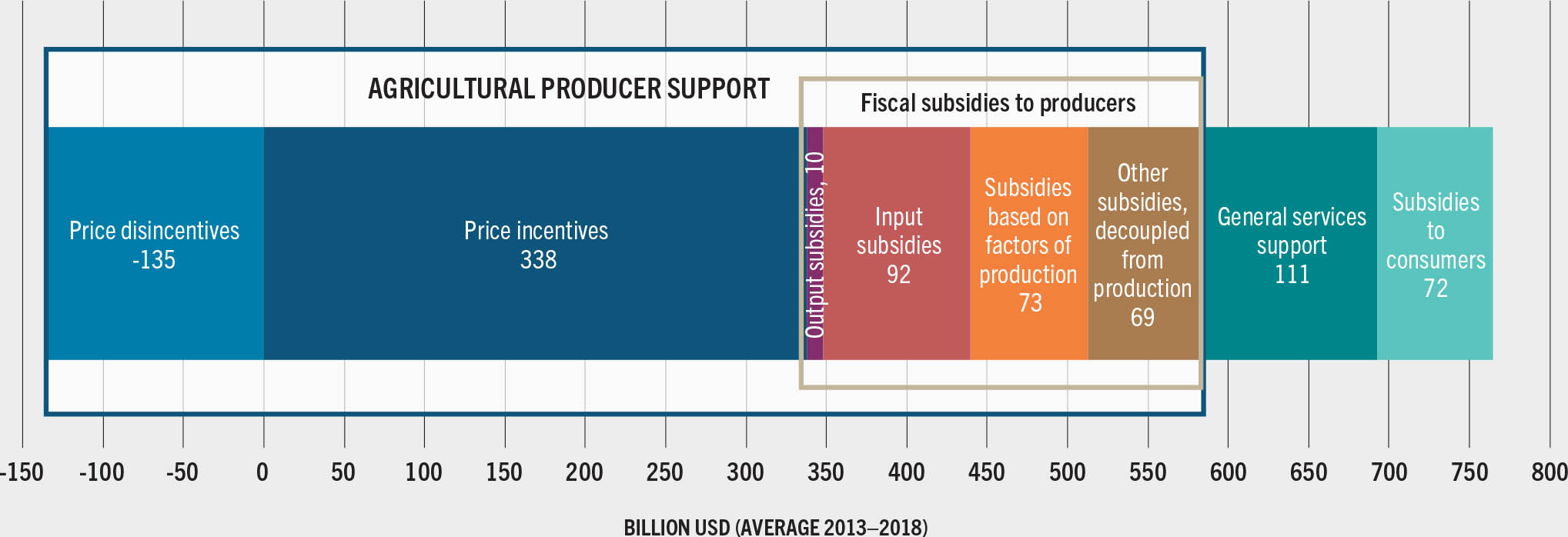

In this blog, we explore how these policies have been put into practice, focusing on Figure 18 from the FAO report:

FIGURE 18 LEVEL AND COMPOSITION OF GLOBAL SUPPORT TO FOOD AND AGRICULTURE (USD BILLION, AVERAGE 2013–2018)

SOURCE: Ag-Incentives. (forthcoming). Ag-Incentives. Washington, DC. Cited 4 May 2022. http://ag-incentives.org with data from OECD, FAO, IDB and World Bank compiled by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Image source: FAO.

Some key takeaways from this analysis (based on the figure and text) can be disaggregated based on the key elements of the food system:

Agricultural producers

- Globally, agricultural producers received, on average from 2013-18, over $550 billion of government support through price incentives (over $300 billion) and fiscal subsidies (about $250 billion)

- This amounts to about 70% of all policy support going to food systems.

- From a production standpoint, rice, sugar and meats are most incentivized worldwide, while producers of fruits and vegetables are less supported overall or are even penalized in some LICs.

- It is important to note the differences in how these policies are implemented in High Income and Upper Middle Income Countries (HIC, UMIC) vs. Lower Middle Income (LMIC) and Low Income Countries (LIC):

- HIC/UMIC: support is mostly through border measures and fiscal subsidies. The support for production focuses on staple foods, dairy and other protein-rich foods.

- LMIC/LIC: subsidies for producers are limited because of budgetary constraints. fiscal space to provide subsidies is more limited and trade policies are normally used to protect consumers from high prices.

Food environment

- General Services Support, on average from 2013-18, accounted for less than 15% (~$110 billion) of government support

Consumers

- Fiscal subsidies to consumers, on average from 2013-18, accounted for less than 10% (~70 billion) of government support

Implications

- While these policies are helpful and necessary, they are not sufficient to meet the needs to food system stakeholders, as evidenced by the fact that 2.3 billion people were food insecure in 2021. There are two dimensions to the insufficiency of these policies:

- more funding is needed for all of them

- the distribution of funding does not address the key priorities of food insecure people and sometimes creates skewed markets

The first point is straightforward, though not easy to implement in practice, but there are some nuances around the second point.

The very skewed distribution of public finances to the agricultural sector has also meant less available for General Services Support and Fiscal Subsidies for consumers, especially in LICs and LMICs, which are essential for addressing acute and chronic food insecurity. Further to this, the fiscal subsidies to agricultural producers and market price controls have increased the availability and reduced prices of food items but they have mostly targeted staple foods like wheat, maize, rice and sugar. This has meant that there are often times disincentives to produce other foods, especially vegetables/fruits and pulses, that are necessary for healthy diets. It has also affected the diversity of foods available, which means that eating a healthy/sustainable diet in these settings ends up being unaffordable for large proportions of the population.

Given the pressures facing individuals and food systems globally because of the after effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns, global inflation, recessions and the Ukraine war, there needs to be a serious rethink of the design, focus and implementation of public sector support to food systems. There should be a shift to disincentivise the production of animal-based products and the resources freed up through these measures could then support the production of healthier/more sustainably produced food items, especially fruits/vegetables and pulses. The resources freed up from a disinvestment in animal products could also be used to increase support for General Services Support and Fiscal Subsidies for Consumer, especially in LICs and LMICs.

These will not be easy moves to make but the implications of not making these shifts will likely mean an increasing burden of food insecurity for citizens across the world.